A study on the discovery of neutralizing antibodies to block the hepatitis C virus entitled, “Broadly neutralizing antibodies abrogate established hepatitis C virus infection” may offer a potential therapeutic approach to interfere with HCV infection by inhibiting the hepatocytes invasion — a key step for chronic infection. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine by Dr. Yep P. de Jong, first author of the work, and part of Dr. Alexander Ploss’ group from the Center for the Study of Hepatitis C, Laboratory of Virology and Infectious Disease, The Rockefeller University, NY.

A study on the discovery of neutralizing antibodies to block the hepatitis C virus entitled, “Broadly neutralizing antibodies abrogate established hepatitis C virus infection” may offer a potential therapeutic approach to interfere with HCV infection by inhibiting the hepatocytes invasion — a key step for chronic infection. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine by Dr. Yep P. de Jong, first author of the work, and part of Dr. Alexander Ploss’ group from the Center for the Study of Hepatitis C, Laboratory of Virology and Infectious Disease, The Rockefeller University, NY.

Prof. Alex Ploss, molecular biology assistant, senior co-author of the study, explained that continuing to advance the treatment of the hepatitis C virus is critical to public and world health doe to the high number of people who have the infection. It is estimated that approximately 150 million people throughout the world have chronic hepatitis C, with an estimated 3 to 4 million in the US alone. Chronic infection in HCV occurs because the virus is continually mutating to evade the immune system. “This can go on for decades,” said Prof. Ploss.

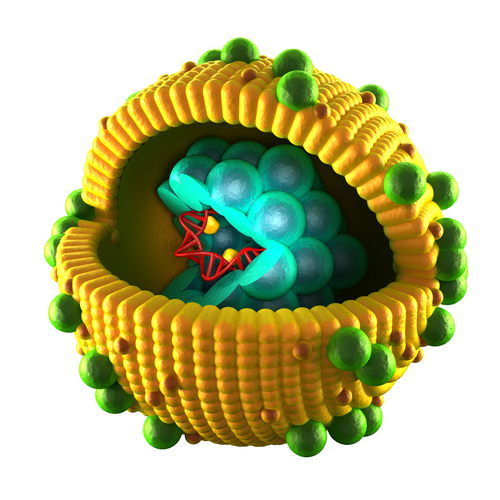

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) works be establishing a chronic infection in most infected individuals, which eventually leads to the development of liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. According to the World Health Organization, the infection is typically the result of “unsafe injection practices; inadequate sterilization of medical equipment in some health-care settings; and unscreened blood and blood products.”Dr. Mansun Law, a co-author of the study, described the virus as a “silent killer” because many people are infected but do not know unless they take a blood test.

The role of antibodies directed against HCV in disease progression is poorly understood. The researcher team found that neutralizing antibodies (nAbs), discovered by co-author Mansun Law and other researchers at the Scripps Research Institute, can prevent HCV infection in vitro and in animal models. In this study, they used mice with a humanized liver, i.e. a mouse liver that has had human liver cells inserted into it, since hepatitis C viruses can only infect humans and primates, which are not allowed to be used for testing.

The researchers had two groups of mice, one treated with normal antibodies and one with the broadly neutralizing antibodies. While the hepatitis C virus is very evasive and hard to treat because of its ability to mutate and change, the team found that the virus could not evade the broadly neutralizing antibodies through mutations. Rather, it was observed that after sequencing the virus and the regions of the envelope, there were no adaptive mutations within the 12 mice studied, meaning that the antibodies contained the virus.

“What we were looking for was, ‘Were there any mutations in the HCV that allowed the HCV to essentially escape from basically being neutralized by the antibodies themselves?’ and what we found was that there weren’t any,” said Dr. Benjamin Winer.

Sherif Gerges, a research specialist that worked on the study, explained that the antibodies worked because the virus’ envelope, its outer coat used to enter the cells, does not mutate as much as the rest of the virus.

“There are regions within this coat that are targets or potential targets for these antibodies,” said Dr. Gerges.

According to The Princetonian’s article, “Professor helps identify antibody as key to fighting hepatitis C,” “the team found that after sequencing the virus and the regions of the envelope, there were no adaptive mutations within the 12 mice studied, meaning that the antibodies contained the virus.”

“It is very interesting to contemplate potentially successful methods for inducing immune responses that protect against hepatitis C viral infection,” highlighted Dr. Cox.

There are current therapies that are can eliminate the virus but are very expensive and do not prevent reinfection by the virus and liver damage, stated Prof. Ploss. It is not known if these findings can be translated to humans but they are promising as regarding a potential new approach to prevent hepatitis C.

“This is a promising potential strategy for developing protection from hepatitis C virus infection that I think is worth further exploration,” concluded Dr. Cox.