Johns Hopkins researchers may have found weak spots in outer coverings of different hepatitis C virus strains that would allow them to be attacked and neutralized by antibodies. The study, titled, “Naturally selected hepatitis C virus polymorphisms confer broad neutralizing antibody resistance” appeared in the January 2015 issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation , and may explain why different people have varying degrees of susceptibility to hepatitis C infection. The research could also suggest potential solutions for creating a hepatitis C vaccine.

, and may explain why different people have varying degrees of susceptibility to hepatitis C infection. The research could also suggest potential solutions for creating a hepatitis C vaccine.

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease of the liver that can be mild to severe. Infection in some people lasts a few weeks while for others a lifetime, leading to serious illness that severely damages the liver.

According to Justin Bailey, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases in the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, there is no individual antibody that can attack all kinds of hepatitis C virus strains. This may be the reason for which only one-third of people clear the virus from their body, while other people suffer from chronic disease.

Bailey and his colleague, Stuart C. Ray, M.D., professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases in the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, along with other scientists studied 18 antibodies that attack the hepatitis C virus and compared them to 19 strains of virus that are responsible for 94 percent of hepatitis C virus genetic variability. All of the strains were from the most common genetic group, known as genotype 1.

The scientists were able to identify three main groups of antibodies, based on their tendency to attack the same viral strain subsets. But what was common about these groups?

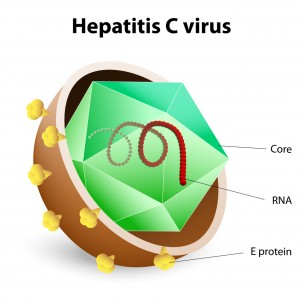

It turned out to have something to do with the viral envelopes that make up the viruses’ outer covering. Depending on how the covering was composed by proteins, the virus would be rendered susceptible to different antibody groups.

The researchers then tested blood plasma samples from 18 people who were chronically infected with hepatitis C. The viral variations leading to antibody resistance in hepatitis C studied in a dish in the lab predicted antibody resistance in the plasma of these infected individuals. The lab studies were then confirmed by actual infected patients.

According to Bailey, this means that a vaccine needs to be ideally tailored to account for all of the genetic diversity that occurs in the virus. Antibody combinations will likely be needed in order to develop a vaccine. Bailey remarked, “We can now start to identify antibodies from different clusters that are likely to be complementary to each other in their neutralizing ability, rather than using antibodies from just a single cluster.”