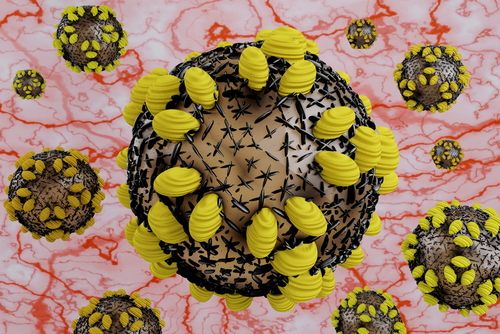

Manipulating the major protein of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) allows the virus to be exposed in a way that the immune system can efficiently detect and attack it. This finding can help improve knowledge behind virus behavior and help in the development of a preventive vaccine for HCV infection.

The results were recently published in the journal Hepatology in a study titled “The core domain of hepatitis C virus glycoprotein E2 generates potent cross-neutralizing antibodies in guinea pigs.”

The genetic sequence of HCV is highly variable, which makes its detection and treatment difficult to standardize and work efficiently.

Direct acting antiviral (DAA) agents, such as Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir), Harvoni (ledipasvir/sofosbuvir), or Daklinza (daclatasvir) were shown to effectively treat about 95 percent of patients. However, they cannot prevent reinfection and can be very expensive.

Three percent of the world’s population is infected with HCV and reinfection is a major concern. And people with undiagnosed HCV are key players in the spread of the disease. As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes that development of preventive vaccines for HCV is a priority.

HCV has the ability to block the immune system’s response by inducing the production of noneffective antibodies. In the current study, researchers from the Burnet Institute in Australia showed that it’s possible to overcome this process.

“What we’ve done is to redirect the immune response to the parts of the virus that you want the immune system to see, and those are the parts that generate broadly cross-reactive antibodies effective against all seven circulating genotypes of virus,” said Heidi Drummer, senior author of the study, in a press release.

This was the first study demonstrating that re-engineering the HCV structure may allow its detection by the immune system in a way that will produce antibodies that can recognize all the known subgroups of the virus. This new immune response against HCV was able to block the virus from entering the cells and infecting them, the authors said.

“That gives us a lead that we can work with to produce a vaccine candidate that’s going to be amenable for a clinical trial,” Drummer said.

According to Drummer, a vaccine would ideally be introduced into existing regimens — for example, as part of a hepatitis A, B, and C vaccine combination in infants, or administered in combination with the human papilloma virus (HPV) in adolescents.