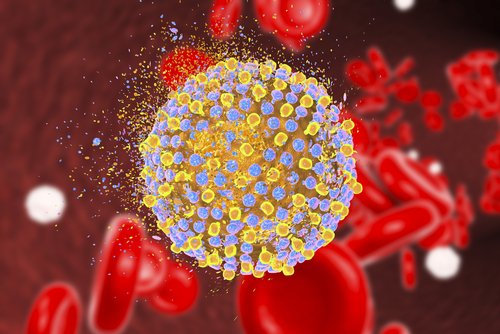

The hepatitis C virus hijacks proteins involved in key signaling pathways to help it survive and grow in the body, according to Australian researchers who identified the proteins.

New treatments for HCV could evolve from the findings, the team said. The virus is a serious disease that can lead to major liver problems, including hepatitis, cirrhosis and cancer.

A team from Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute spearheaded the study, titled “Signalome-wide assessment of host cell response to hepatitis C virus.” It was published in the journal Nature Communications.

The findings built upon a study that Monash published in 2011. It showed that the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum harnesses proteins in the body of the person it is infecting to help it survive and grow.

Professor Christian Doerig, the senior author of the study, reported that the parasite, a protozoa, needed to marshal protein kinases – or enzymes that regulate cell function – in order to survive.

The findings prompted the team to do another study. This time the researchers sought to determine which kinases and other proteins were involved in the cell signaling the parasite needed to harness to survive. The Monash scientists did this study in collaboration with the Canadian-based company Kinexus.

Researchers found “a number of new cell signaling pathways that were activated or suppressed by an HCV infection,” Doerig said in a press release.

Altogether, they identified 103 genes that appeared to play a role in HCV’s ability to copy itself, or replicate. To validate the findings, the team genetically inhibited each gene. Their thought in doing that was that if a gene were essential to the virus’ survival, then silencing it would impair its ability to replicate.

Researchers discovered that HCV hijacked several proteins involved in key signaling pathways to ensure that it could copy itself.

The team then used a compound that Harvard University Professor Nathanael Gray discovered to take their research further. The compound blocks the activity of one of the kinases that HCV must harness to replicate.

“Nathanael sent us his new molecule, and we put it in our host cells, infected them with HCV and found that while the cells were fine, they didn’t support virus replication anymore,” said Reza Haqshenas, lead author of the study.

The findings suggest that researchers could use signaling pathways to develop therapies against viruses and bacteria.

“The platform we have established can be adopted to identify new anti-infective compounds against any pathogens — including, viruses, bacteria and parasites — that invade mammalian cells,” Haqshenas said.

The team plans to continue its work in studies involving the Zika virus and toxoplasmosis infections.

Hepcinat Plus New Treatment of Hepatitis C