It has been proved that individuals who are infected with the hepatitis C virus are more prone to liver damage. Now, according to recent results from a Johns Hopkins study, this infection might also result in cardiac complications.

The results were published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases and emerged from a bigger ongoing study that included men who have sex with men, many (not all) of whom were infected with HIV. These subjects were assisted over time to evaluate the risk of infection and disease progression. A group of subjects who participated in the study had both hepatitis C and HIV (these 2 infections frequently occur together).

It is already known that carrying HIV infection increases patients’ risk for heart disease but researchers now explain how hepatitis C, independently of HIV, can also trigger cardiovascular damage.

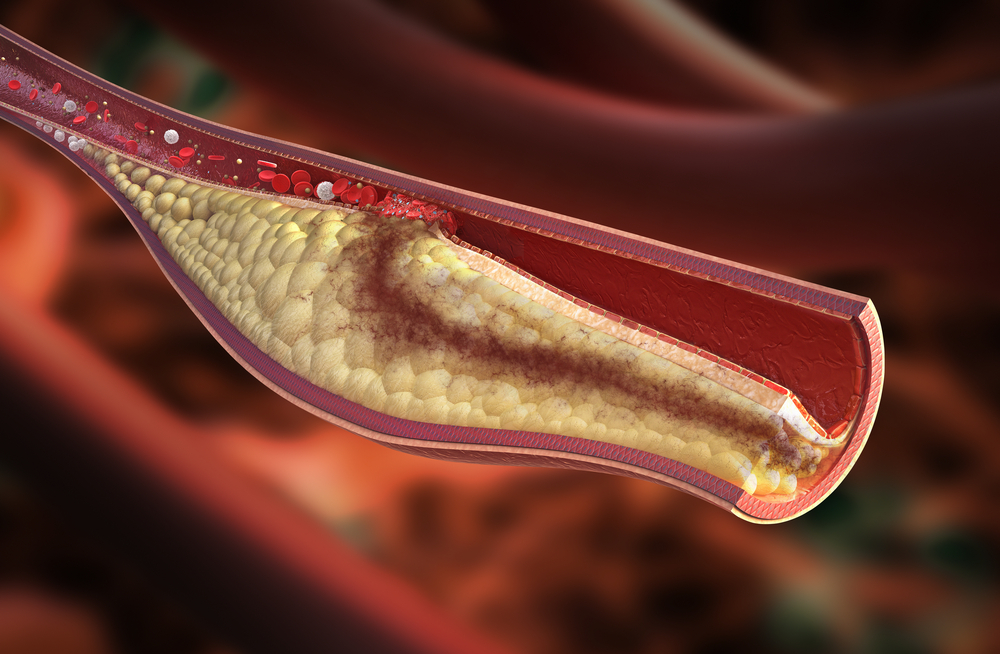

Researchers found that those chronically infected with hepatitis C were more likely to pile up abnormal fat-and-calcium plaques in their arteries (atherosclerosis), which could lead to heart attacks and strokes. “We have strong reason to believe that infection with hepatitis C fuels cardiovascular disease, independent of HIV and sets the stage for subsequent cardiovascular trouble. We believe our findings are relevant to anyone infected with hepatitis C regardless of HIV status,” explained the study’s principal investigator Eric Seaberg, from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The reason why the infection results in artery-clogging plaque is not clear but evidences of the phenomenon are quite strong. “People infected with hepatitis C are already followed regularly for signs of liver disease, but our findings suggest clinicians who care for them should also assess their overall cardiac risk profile regularly,” noted Wendy Post, one of the study’s authors.

A total of 994 between the ages of 40 to 70 and without evidence of heart disease were followed in several institutions in Washington, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, D.C., Los Angeles and Chicago. Of these patients, 613 were infected with HIV, 70 with both viruses and 17 were only infected with hepatitis C. Participants had cardiac CT scans to measure the percentage of calcium and fat deposits inside their heart vessels, and those infected with hepatitis C, regardless of their HIV status, showed on average 30 percent more calcified plaques; those with hepatitis C or HIV had, on average, 42 percent more non-calcified fatty buildup.

Patients with elevated levels of circulating hepatitis C virus in the blood were 50 percent more prone to present clogged arteries, in comparison to men without hepatitis C. When higher virus levels are present in the blood, signs of uncontrolled infection begin to appear, which may contribute to heart disease development.

Treating hepatitis C infection in an early stage of the disease can fight off long-term liver damage, however researchers explain their findings raise critical questions: whether a new class of medications that helps 90 percent of individuals to erase the virus within a few short months could also stop the formation of plaques and significantly decrease cardiac risk.